What is social entrepreneurship?

The relationship with profit is one of the aspects that differentiate social entrepreneurship from ordinary entrepreneurship

Rawpixel image available on Unsplash

Social entrepreneurship is a form of entrepreneurship whose main objective is to produce goods and services that benefit local and global society, with a focus on social problems and the society that most closely faces them.

Social entrepreneurship seeks to rescue people from situations of social risk and promote the improvement of their living conditions in society, through the generation of social capital, inclusion and social emancipation.

the question of profit

Profit is one of the aspects that differentiate ordinary entrepreneurship from social entrepreneurship. For the average entrepreneur, profit is the entrepreneur's driver. The joint venture's purpose is to serve markets that can comfortably pay for the new product or service. Therefore, this type of business is designed to generate financial profit. From the beginning, the expectation is that the entrepreneur and his investors will obtain some personal financial gain. Profit is the essential condition for the sustainability of these ventures and the means to their ultimate end in the form of large-scale market adoption.

- What is sustainability: concepts, definitions and examples

The structure of social entrepreneurship

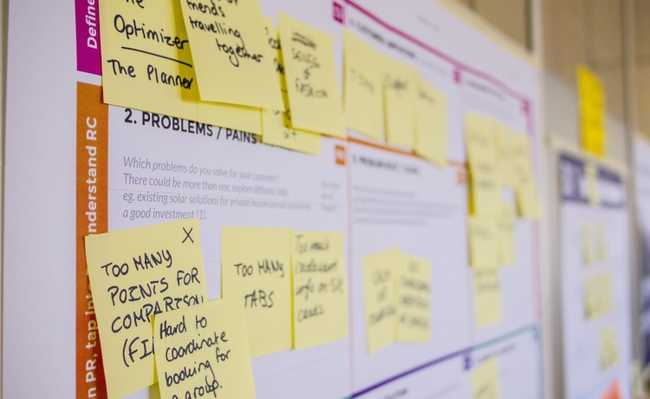

Edited and resized image of Daria Nepriakhina, is available on Unsplash

Social entrepreneurship consists of three main components:

- The identification of a stable but inherently unfair balance that causes the exclusion, marginalization or suffering of a segment of humanity that does not have the financial means or political influence to achieve any transformative benefit for itself;

- Identifying an opportunity in this unfair balance, developing a social value proposition and bringing inspiration, creativity, direct action, courage and fortitude, thus challenging the stable state hegemony;

- Create a new stable balance that releases untapped potential or alleviates the suffering of the target group, through the creation of a stable ecosystem, ensuring a better future for the target group and even for society in general.

The French economist Jean-Baptiste Say, in the beginning of the 19th century, described the entrepreneur as that person who "transfers economic resources from a lower area to an area of higher productivity and higher income".

A century later, Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter built on this basic concept of value creation, contributing to what is arguably the most influential idea about entrepreneurship. Schumpeter identified in the entrepreneur the strength needed to drive economic progress and said that without them, economies would become static, structurally immobilized and subject to decay. Within Schumpeter's definition, the entrepreneur identifies a business opportunity - be it a material, product, service or business - and organizes an enterprise to implement it. Successful entrepreneurship, he argues, sets off a chain reaction, encouraging other entrepreneurs to repeat and propagate innovation to the point of “creative destruction”, a state in which the new venture and all its related companies effectively transform existing products and services. , as well as obsolete business models.

Despite being heroic, Schumpeter's analysis supports entrepreneurship within a system, attributing to the role of the entrepreneur a paradoxical impact, both disruptive and generative. Schumpeter sees the entrepreneur as an agent of change within the larger economy. Peter Drucker, on the other hand, does not see entrepreneurs as necessarily change agents, but as smart and committed explorers of change. According to Drucker, “the entrepreneur always looks for changes, responds to them and explores it as an opportunity”, a premise also adopted by Israel Kirzner, who identifies “attention” as the most critical skill of the entrepreneur.

Regardless of whether they cast the entrepreneur as an innovator or an early explorer, theorists universally associate entrepreneurship with opportunity. Entrepreneurs are believed to have an exceptional ability to see and seize new opportunities, the commitment and motivation required to pursue them, and an unwavering willingness to take the inherent risks.

What differentiates ordinary entrepreneurship from social entrepreneurship is simply motivation - the first group is driven by money; the second, for altruism. But according to Roger L. Martin & Sally Osberg, the truth is that entrepreneurs are rarely motivated by the prospect of financial gain, because the chances of making a lot of money are rare. For him, both the average entrepreneur and the social entrepreneur are strongly motivated by the opportunity they identify, relentlessly pursuing this vision and obtaining considerable psychic reward from the process of realizing their ideas. Regardless of whether they operate in a market or in a non-profit context, most entrepreneurs are never fully compensated for their time, risk and effort.Examples of social entrepreneurship

Muhammad Yunus

Muhammad Yunus, founder of Grameen Bank and father of microcredit, is a classic example of social entrepreneurship. The problem he identified was the limited ability of the poor in Bangladesh to secure even the smallest amounts of credit. Unable to qualify for loans through the formal banking system, they could only borrow at exorbitant interest rates from local moneylenders. The result is that they simply ended up begging in the streets. It was a stable equilibrium of the most unfortunate kind, which perpetuated and even exacerbated Bangladesh's endemic poverty and the resulting misery.

Yunus confronted the system, proving that the poor had an extremely low credit risk by lending the amount of $27 out of their own pocket to 42 women in the village of Jobra. The women paid off the entire loan. Yunus found that, even with small amounts of capital, women invested in their own ability to generate income. With a sewing machine, for example, women could sew clothes, earning enough to pay off the loan, buy food, educate their children, and lift themselves out of poverty. Grameen Bank supported itself by charging interest on its loans and then recycling the capital to help other women. Yunus brought inspiration, creativity, direct action and courage to his venture, proving its viability.

Robert Redford

Famous actor, director and producer Robert Redford offers a less familiar but also illustrative case of social entrepreneurship. In the early 1980s, Redford gave up his successful career to regain space in the film industry for artists. He identified an inherently oppressive but stable balance in the way Hollywood worked, with its business model increasingly driven by financial interests, its productions being geared towards blockbusters flashy, often violent, and its studio-dominated system becoming increasingly centralized in controlling how films were financed, produced, and distributed.

Seeing all this, Redford took the opportunity to nurture a new group of artists. First, he created the Sundance Institute to raise money and provide young filmmakers with space and support to develop their ideas. Then he created the Sundance Film Festival to showcase the work of independent filmmakers. From the beginning, Redford's value proposition focused on the emerging, independent filmmaker whose talents were not recognized or catered for by the market dominance of the Hollywood studio system.

Redford structured the Sundance Institute as a non-profit corporation, encouraging its network of directors, actors, writers and others to contribute their experience as volunteer mentors to novice filmmakers. He priced the Sundance Film Festival so that it would be accessible to a wide audience. Twenty-five years later, Sundance became a reference in the release of independent films, which today guarantees that filmmakers “indie” can produce and distribute their work - and that North American viewers have access to a range of options, from documentaries to international works and animations.

Victoria Hale

Victoria Hale is a pharmaceutical scientist who has become increasingly frustrated with market forces dominating her field. Although the big pharmaceutical companies held patents on drugs capable of curing countless infectious diseases, the drugs were not developed for a simple reason: the populations that most needed these drugs could not afford them. Driven by the demand to generate financial profits for its shareholders, the pharmaceutical industry was focused on creating and marketing drugs for diseases that afflict the rich, living mainly in developed world markets, which could pay for them.

Hale decided to challenge this stable balance, which she considered unfair and intolerable. She created the Institute for OneWorld Health, the world's first non-profit pharmaceutical company whose mission is to ensure that drugs targeting infectious diseases in the developing world reach the people who need them, regardless of their ability to pay for them. Hale has successfully developed, tested and secured regulatory approval from the Indian government for its first drug, paromomycin, which provides a cost-effective cure for visceral leishmaniasis, a disease that kills more than 200,000 people each year.

Social entrepreneurship is different from social care and activism

There are two forms of socially valuable activities that are different from social entrepreneurship. The first of these is the provision of social service. In this case, a brave and committed individual identifies a social problem and creates a solution to it. The creation of schools for orphaned children who have the HIV virus is an example in this regard.

However, this type of social service never goes beyond its limits: its impact remains limited, its area of service remains confined to a local population, and its scope is determined by whatever resources they are able to attract. These ventures are inherently vulnerable, which can mean disruption or loss of service for the populations they serve. Millions of these organizations exist around the world - well intentioned, noble purpose and often exemplary - but they should not be confused with social entrepreneurship.

It would be possible to redesign a school for orphans who have the HIV virus as social entrepreneurship. But that would require a plan whereby the school itself would create an entire network of schools and secure the foundation for their continued support. The result would be a new, stable balance whereby, even if a school closed, there would be a robust system in place through which children would receive needed services on a daily basis.

The difference between the two types of entrepreneurship - one social entrepreneurship and the other social service - is not in the initial entrepreneurial contexts or in the personal characteristics of the founders, but in the results.

A second class of social action is social activism. In this case, the motivator of the activity has inspiration, creativity, courage and strength, just like in social entrepreneurship. What sets them apart is the nature of the actor's action orientation. Instead of acting directly, as the social entrepreneur would, the social activist tries to create change through indirect action, influencing others - governments, NGOs, consumers, workers, etc. - to act. Social activists may or may not create businesses or organizations to bring about the changes they seek. Successful activism can produce substantial improvements to existing systems and even result in a new balance, but the strategic nature of action is geared towards its influence rather than direct action.

Why not call these people social entrepreneurs? It wouldn't be a tragedy. But these people have long had a name and an exalted tradition: the tradition of Martin Luther King, Mahatma Gandhi, and Vaclav Havel. They were social activists. Calling them something totally new - that is, social entrepreneurs - and thus confusing the general public, who already know what a social activist is, would not be helpful.

Why should we care?

Long rejected by economists, whose interests have turned to market models and prices, which are more readily subject to data-driven interpretation, entrepreneurship has experienced something of a renaissance in recent years.

However, serious thinkers have ignored social entrepreneurship and the term has been used indiscriminately. But the term deserves more attention, as social entrepreneurship is one of the tools available to alleviate the problems of current society.

The social entrepreneur must be understood as someone who observes the negligence, marginalization or suffering of a segment of humanity and finds in this situation inspiration to act directly, using creativity, courage and strength, establishing a new scenario that ensures permanent benefits for this group target and for society in general.

This definition helps to distinguish social entrepreneurship from the provision of social services and social activism. However, nothing prevents social service providers, social activists and social entrepreneurs from adapting to each other's strategies and developing hybrid models.

Adapted from Social Entrepreneurship: The Case for Definition